At first light, the mountains awaken. A pale glow spreads across the icy crown of Manaslu, and the air carries the faint hum of prayer wheels turning in distant villages. Down in the valley, smoke rises from stone hearths as herders lead their yaks towards the river. It is here, in this stillness between earth and sky, that the Manaslu Circuit begins: a journey into Nepal’s hidden heart where remoteness, beauty, and endurance shape every step. Unlike the crowded trails of Everest or Annapurna, the Manaslu region remains a sanctuary of quiet paths and untouched culture, a place where solitude feels profound rather than lonely, and the rhythm of the mountains dictates the pace of each day.

Manaslu itself, the eighth-highest mountain on Earth at 8,163 metres, takes its name from the Sanskrit word for “Mountain of the Spirit.” It rises like a vast white pyramid above the valleys, born from the collision of tectonic plates that began fifty million years ago when the Indian subcontinent drove northward into Eurasia. The Himalayas are still rising, still being shaped by forces deep beneath the crust. Glaciers carve the high valleys; the Budhi Gandaki River has spent millennia cutting through limestone and schist, creating gorges so narrow that sunlight reaches the trail only at midday. This is geology made visible: a landscape still becoming.

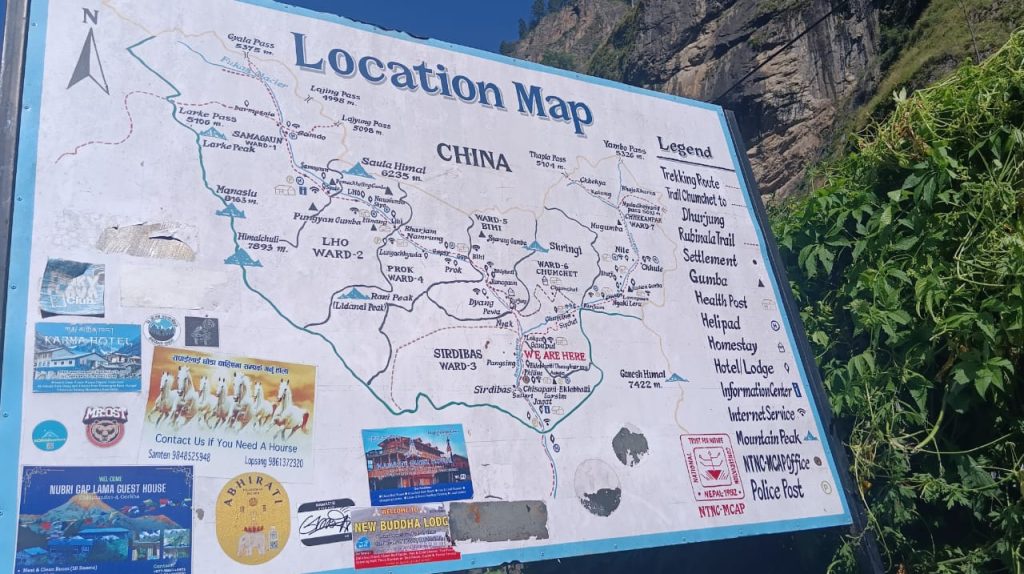

The route winds through the Budhi Gandaki valley, climbing gradually from Soti Khola’s warm lowlands to the high passes that touch the clouds. Over thirteen to sixteen days, trekkers cross a living landscape that shifts from rice terraces to glacial ridges. The circuit rises to its highest point at Larke La Pass, 5,106 metres above sea level, before descending through pine forests and open meadows towards Dharapani. The trek is classed as moderate to challenging, best undertaken between March and May or from September to November, when the skies are clear and the mountain light sharpens every contour. In spring, the lower forests blaze with rhododendron blooms: crimson, pink, and white against the green. In autumn, the air is crystalline, the peaks sharp as cut glass. The monsoon months bring landslides and leeches; winter seals the high passes under snow. As the region lies within a restricted area bordering Tibet, trekkers must travel with a licensed guide and carry permits for the Manaslu and Annapurna Conservation Areas.

Each stage reveals a different world. From Soti Khola to Machha Khola, the trail moves through dense forest and terraced farmland where the sound of rivers fills the air. The Budhi Gandaki roars through narrow gorges, its water milky with glacial silt. Suspension bridges sway underfoot, prayer flags strung across their cables snapping in the wind. In the villages of Jagat and Deng, stone walls are carved with Tibetan mantras, and prayer flags ripple above narrow lanes. The architecture begins to shift: Hindu stone houses give way to Tibetan wooden structures with intricately carved windows and flat roofs stacked with firewood. Higher still, Namrung and Lho open to vast views of Manaslu’s icy pyramid rising above ancient monasteries. At Samagaon, a resting point for acclimatisation, the mountain dominates the horizon like a silent guardian.

Samagaon sits at 3,530 metres, and here the body begins to feel the altitude. Breath comes shorter; the heart works harder. Acclimatisation days are not optional but necessary, allowing red blood cells to multiply and adjust to the thinning air. Trekkers can visit Pung Gyen Gompa, perched on a ridge where the wind carries the chants of monks and the scent of juniper incense. Inside, butter lamps flicker before gilded statues, and thangkas depicting wrathful deities hang from the walls. Or they can hike towards Manaslu Base Camp, following moraine ridges to glimpse the glaciers gleaming in the afternoon sun, their surface cracked and blue, ancient ice moving imperceptibly downslope.

From Samagaon, the trail climbs through Samdo, a village so close to Tibet that yak herders speak both Nepali and Tibetan dialects. This was once part of the salt trade route, where caravans crossed the high passes carrying grain north and salt south, a trade that sustained these communities for centuries. The 2015 earthquake shattered much of this region: homes collapsed, trails were buried, and lives were lost. Yet the people rebuilt, stone by stone, their resilience as enduring as the mountains themselves.

Beyond Samdo lies Dharamsala, also called Larkya Phedi, the last teahouse before the pass. At 4,460 metres, the air is thin and cold. Trekkers rise before dawn, headlamps bobbing in the darkness, breath steaming in the frigid air. The climb to Larke La begins in blackness, the trail switchbacking up scree slopes where frost crunches underfoot. As the sun rises, the peaks ignite: first pink, then gold, then blazing white. The pass itself, at 5,106 metres, is a wind-scoured saddle where peaks stretch endlessly in every direction. To the north, the Tibetan plateau; to the south, the valleys of Nepal. Prayer flags snap violently in the wind, and the cold cuts through every layer of clothing. Yet standing here, lungs burning, legs trembling, there is a profound sense of arrival. The world feels vast and intimate at once.

The descent is long and steep, dropping over 1,600 metres to Bimthang through a landscape of rock and ice. Knees ache; trekking poles dig into loose scree. But gradually the world softens. Grass appears, then juniper bushes, then the first stunted pines. By the time the trail reaches Bimthang, the air feels thick and rich again, almost intoxicating after days in the thin atmosphere above. From here, the path continues through Tilije and Dharapani, where the trail rejoins the Annapurna Circuit. Rhododendron forests close in, streams tumble over mossy rocks, and the scent of pine fills the air.

The journey is not only a passage through landscapes but through culture. The Manaslu region remains deeply rooted in Tibetan Buddhism, and the influence is felt in every village and every prayer stone that lines the trail. In places like Lho and Samdo, life moves at a pace unchanged for centuries. Monasteries stand on ridges where the clouds drift like slow-moving rivers, and chortens mark the paths with quiet blessings. Women spin prayer wheels as they walk, their lips moving in silent mantra. Yaks graze on slopes so steep it seems impossible they don’t tumble into the valleys below. Blue sheep, near-mythical creatures with curved horns, watch from rocky outcrops. In the lower forests, red pandas move through the canopy, though they are rarely seen. Higher still, snow leopards hunt in solitude, ghosts of the high peaks.

Hospitality in these mountains is genuine and unassuming. Teahouses offer warmth in the form of dal bhat, butter tea, and a place beside the stove, where stories are exchanged in the soft glow of firelight. The dal bhat is simple but nourishing: rice, lentil soup, vegetable curry, sometimes a bit of pickle or yogurt. Butter tea, salty and rich, is an acquired taste, but at altitude it provides calories and warmth. Tsampa, roasted barley flour mixed into tea or milk, is the staple food of high-altitude peoples, dense and sustaining. In these small rooms, wooden benches arranged around a central stove, trekkers sit shoulder to shoulder with guides, porters, and locals. Conversations unfold slowly, aided by gesture and laughter when language fails. It is in these small rooms that trekkers begin to understand the generosity and resilience of those who call this region home.

The porters and guides who make this journey possible are often from villages along the route. They carry loads that would break most Western backs: thirty, forty, sometimes fifty kilograms balanced in wicker baskets supported by a tumpline across the forehead. They walk in worn sneakers or sandals, while trekkers stumble along in expensive boots. Their knowledge of the terrain, the weather, and the mountains is encyclopedic. They know which teahouse has the warmest rooms, which streams are safe to drink from, when a storm is building over the ridge. Their kindness and patience are inexhaustible. Many have walked these trails since childhood, following fathers and grandfathers into the mountains. To trek the Manaslu Circuit without acknowledging their labour and skill would be to miss half the story.

Practical preparation is essential. Three permits are required: one for restricted entry and two for conservation areas, all arranged by us. Accommodation is simple but sufficient, with teahouses providing wooden rooms, blankets, and hearty meals. Packing demands careful thought: layered clothing for temperatures that range from 30°C in the valleys to minus 15°C at the pass, a sleeping bag rated to at least minus 10°C, trekking poles to ease the strain on knees during long descents, and water purification tablets or a filter, as streams above villages may be contaminated. A headlamp is essential for pre-dawn starts. Sunscreen and sunglasses are non-negotiable at altitude, where UV radiation intensifies and snow blindness is a real risk. Above Namrung, connectivity fades; solar power becomes the only source of light, and Wi-Fi is scarce. Yet this very disconnection is part of the trek’s allure: an invitation to live without haste and distraction.

Altitude, weather, and terrain all demand respect. Acute mountain sickness can strike anyone, regardless of fitness. Headaches, nausea, dizziness, and insomnia are early signs. The only cure is descent. Acclimatisation days help the body adjust, and a measured pace prevents fatigue. The old mountain adage holds true: climb high, sleep low. Diamox, a medication that aids acclimatisation, is carried by many trekkers, though it is no substitute for proper pacing and rest. The challenges are real, but so too are the rewards: the stillness of dawn in Samagaon, the clarity of air above the glaciers, and the silent satisfaction that comes from crossing Larke La under a sky alive with wind and light. The trek humbles and uplifts in equal measure. It is a journey that tests resolve but restores a sense of wonder often lost in ordinary life.

From a photographer’s eye, the Manaslu Circuit is a world of contrasts: fluttering prayer flags set against snow peaks, yak caravans winding through frozen passes, suspension bridges stretching across turquoise rivers, and the first light of morning spilling over fields of frost. At Lho, the view of Manaslu from the monastery terrace is one of the finest in the Himalayas: the mountain rising sheer and white, framed by prayer flags that blur in the wind. At Larke La, the light shifts moment by moment, clouds boiling up from the valleys, the peaks emerging and disappearing like phantoms. A map outlines the route, but the true memory of the trek lies in these fleeting moments: the scent of juniper smoke, the echo of bells on a hillside, the shared laughter of strangers around a meal, the taste of salt in butter tea, the ache in the lungs at 5,000 metres, the night sky over Dharamsala so thick with stars it seems possible to reach up and touch them.

Reaching the trailhead requires a long drive from Kathmandu to Soti Khola, a journey of seven to eight hours that itself reveals Nepal’s layered terrain, from bustling valleys to remote hill settlements. The road is rough, winding, often damaged by landslides. Costs vary according to itinerary and agency, averaging between USD 1,800 and 1,900, inclusive of guides, meals, and permits. This includes the guide’s wage (around USD 25 to 30 per day), porter fees if needed, teahouse accommodation (USD 3 to 5 per night), and meals (USD 15 to 20 per day). Permits total around USD 100. Comprehensive travel insurance is vital, and trekkers are urged to follow their guide’s advice carefully, particularly on altitude and weather. The mountains reward patience and respect, not haste.

As the sun sets over Bimthang and shadows lengthen across the valley, a raven circles above the cliffs and the prayer flags flutter in the fading light. The air is thin, yet alive with quiet energy. The Manaslu Circuit becomes a passage through faith, endurance, and the delicate balance of life at the roof of the world. Those who walk its paths leave with something far greater than photographs: a renewed reverence for the mountains and for the strength of the human spirit that rises, breath by breath, towards their summits. The circuit does not conquer the mountains; it teaches humility before them. And in that humility lies a kind of grace.

Copyright © Everest Alpine Trekking 2025